In the average speaking business – whether you’re brand new or an expert on stage – the speaker sales process comes in about nine stages. Starting with “Connected” and ending with “Closed,” these stages cover the steps it takes for you to find a lead, show them your stuff, then get them to hire you. For new speakers, especially, including all nine steps can sound overcomplicated, and it can be tempting to simplify it. But, the intermediary stages – the ones like writing speaker contracts and getting them signed – are some of the most important.

Along these lines, this guide is all about the “Contract” stage in your sales pipeline and how you can write an airtight contract every time. Below, we’ll cover a variety of components to the contract crafting process including what they are, why they’re so crucial in successful speaking businesses, and how you can use them to protect yourself and your clients.

We’ll also break down a few speaker contract examples. That way, the next time one of your leads says, “Let’s make this official!” you can send over a contract with speed and confidence.

What are speaker contracts?

In a nutshell, speaker contracts are print or electronic documents that outline a professional agreement between a speaker and their client. This includes the scope of the work the speaker will undertake for their client, any corresponding due dates for this work, and any circumstances that would prevent these due dates from being met.

Basically, writing speaker contracts involves answering, in detail, a series of questions that the client could answer. For example, a contract should answer “What tasks or number of hours are included in the speaker’s fee?” and “In the event that the speaker can’t fulfill their contract, what happens? Is the client refunded? Does the speaker recommend someone else?” The list of questions can be huge, depending on the project.

With your own contracts, it’s important to, first, pay attention to the questions you hear from clients. Then, as you write more and more contracts, answer those questions or adjust your existing answers to provide more clarity, so your contracts improve as time goes on.

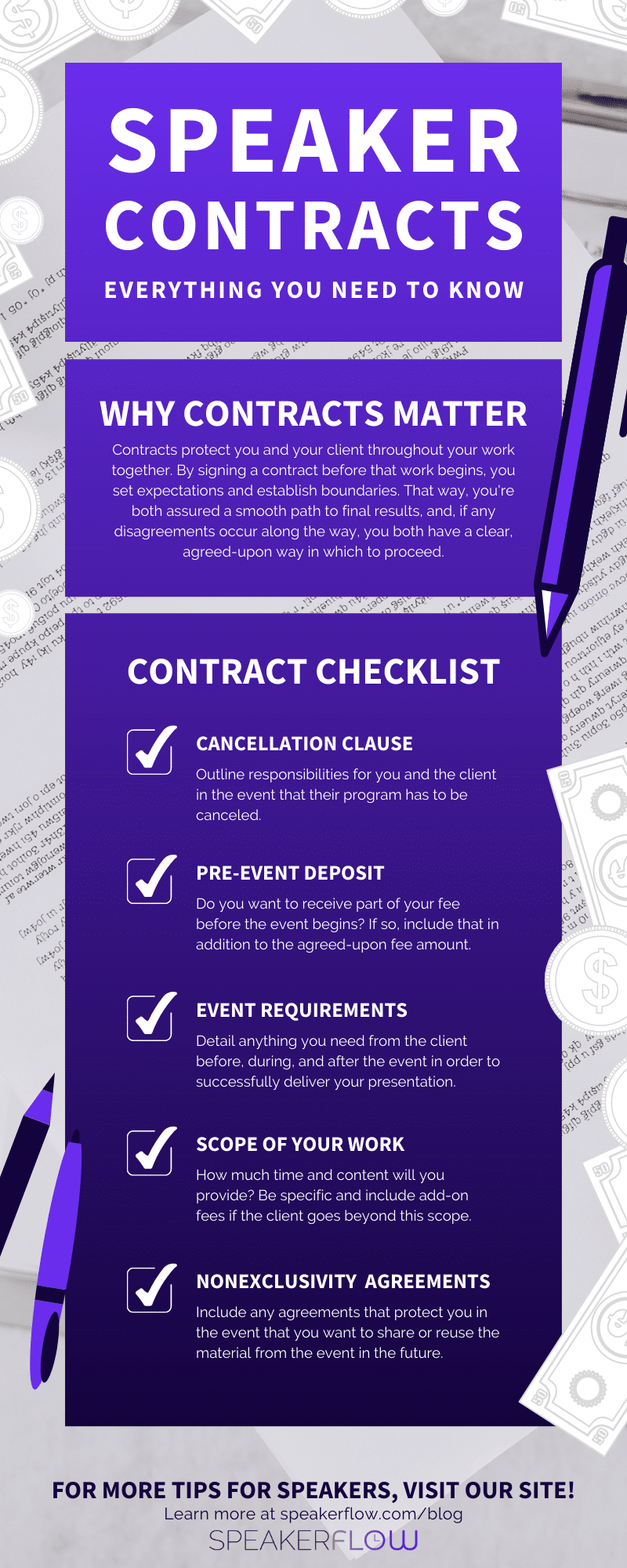

Why are speaker contracts important?

Though the exact layout of a contract can vary from speaker to speaker, all contracts are vitally important, as they protect both the speaker and their client in the event of a misunderstanding or – worst case scenario – a legal dispute. By signing a contract, both parties are prevented from saying they misunderstood the terms of their work together down the road. Additionally, if the project goes out of the contractual scope, the speaker can hold their client legally liable for any relevant added costs.

Because of their legal importance, while writing speaker contracts begin with the speaker’s own words, all contracts should be vetted by a legal professional, too. This ensures that the contract is legally binding and that both parties are confident they’re protected when signing.

How do speaker contracts differ from proposals?

One of the most common questions we hear from our own clients is, “I already have a proposal. How is that different from a contract?”

Simply put, a proposal is much broader than a contract and comes before a contract in the sales cycle. While it should include details about the project at hand, a proposal outlines the basic details only. It also functions as a selling mechanism and should include a description of the client’s problem, how the speaker can solve it, and testimonials from the speaker’s past clients. In this way, a speaker proposal gets a “soft yes” from the client (i.e. an initial confirmation that they want to hire the speaker).

Contracts, on the other hand, are a “hard yes.” Compared to proposals, they’re not only much more detailed about the scope of the project and the related fees. They also include any language, terms, and conditions to make the agreement between the speaker and client legally binding. As such, they should not include any sales jargon or testimonials, just unembellished stipulations.

How do speaker contracts differ for live and virtual events?

Generally speaking, writing speaker contracts is a matter of iteration. As you learn more about what your clients are looking for and what information is needed for seamless work together, you can consistently improve your contracts to make them better reflect your – and your average client’s – expectations.

For the most part, this allows you to use the same basic contract as a template from client to client. However, in the event that you’re speaking virtually, there are a few additional things to include. Below are our recommendations.

- Cancellation Clause: If the event has to be cancelled (due to technical reasons, low attendance, etc.), what do you require in return? Will you be paid the same as if the event had taken place? Do you require a certain amount of time before a cancellation as a heads-up?

- Technological Preferences: Do you have preferred platforms with which to deliver virtual keynotes? If so, include them in this section. If not, state which platform your client has agreed to use.

- Additional Components: Many virtual events come with supplementary resources. If your client requires these add-ons for their event, include details about the scope of said resources in this section.

What should you include in speaker contracts?

That said, regardless of whether you’re speaking for a virtual or live event, there are a handful of tried-and-true elements to include when writing speaker contracts. Below, we’ll break down each of these items along with any recommendations we’ve compiled from our previous clients. That way, you can learn from other speakers’ mistakes and hit the ground running.

Include a cancellation clause.

First, define your expectations should the client want to cancel. Obviously, in an ideal world, this situation doesn’t pop up often. But, if we’ve learned anything from the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, it’s that sometimes cancelling an event is best for everyone involved.

With this in mind, include a clause in your contract that outlines both parties’ responsibilities in the event of a cancellation. Below are a few questions this clause should address.

- What does the cancellation process look like if the client wants to cancel?

- How soon before the event is the client able to cancel? If they cancel after said timeframe is there a cancellation fee?

- If you have to cancel the event, what will the cancellation process look like and what is your designated cancellation timeframe?

- In the event of cancellation, what will you owe to your client? Will you have to refund their initial deposit?

- Are there any actions that automatically signal cancellation?

Pro Tip: When writing speaker contracts, as part of your cancellation clause, include a process disclaimer. This should essentially state that, if the party wishing to cancel the contract doesn’t follow the agreed-upon cancellation process, the other party is no longer liable for their loss.

Decide on a deposit (and a clause in case the event cancels).

Second, it’s time to break down the big topic: your speaking fees. Before any event, it’s imperative that you establish clear expectations for your pay and any additional costs you wish to be covered by the client. This includes fees that you can’t anticipate, like travel expenses. However, to streamline their fees, many speakers opt for speaking packages that account for the vast majority of anticipated costs as well as the cost of the presentation itself.

From there, after deciding how much to charge for your services, explain them in your contract including any pre-event deposit you require in order to “save the date” for their event. All in all, when writing speaker contracts, this section should answer the following questions:

- How much of the total fee is required as a deposit?

- If the event is cancelled by the client, do they receive a refund for their deposit?

- If the event is cancelled by you, does the client receive a refund for their deposit?

- What payment method should the client use to pay the deposit? What method will you use for refunding deposits?

- If the event is postponed, can the deposit be applied to the postponed event rather than being refunded entirely?

Specify what you require pre-, mid-, and post-event.

Third, describe the materials, assistance, and information you need in order to provide the best presentation possible. As with any formal event, the more you can prepare – and the more help you can have from your client – the better your role in the event will be.

It’s also important to focus on your client, on their organization, their needs, their concerns, and their objectives. Then build your list of requirements based on what you need to meet those objectives for them. Below are some questions to help you start.

- Before the event, what background information do you need to know in order to do a good job?

- Traveling to and from the event, will the client cover your travel expenses? If so, are they factored into your total fee and is there a limit?

- During the event, what materials will you need for your presentation? This can include a laptop, HDMI cable, projector, microphone, etc.

- During the event, is the client allowed to record your presentation? If so, are they allowed both audio and video recording?

- After the event, in what timeframe is the client required to pay the remainder of your speaking fee?

Pro Tip: If you’re unsure what to include in this section, the best thing you can do is network. Whether you’re on social media, at a local speakers association meeting, or within your existing network, learn from experienced speakers as much as you can. Chances are the things they have learned to require will also benefit you.

Define the scope of your work for the client.

Fourth, explain everything you will accomplish for your client. In this section, your aim is to make your responsibilities crystal clear for the client reading your contract. They should know exactly what tangible (and intangible) results they’ll receive from you as well as how many hours you’ll spend serving them. Combined, these make up the “scope” of the project. By establishing scope, you prevent clients from demanding more than the agreed-upon results.

To define the scope of the project, start by answering the following questions.

- Pre-event, what aspects of your presentation will you provide to the client for review? This can be as small as your slide deck only or as much as a recorded rehearsal of your presentation.

- Will you participate in activities before or after your presentation is over? These include dinners, meet-and-greets, or even additional speaking appearances, such as panel discussions.

- How long are you required to be on-site before and after the event? While on-site, when and where should you expect to rehearse and run a pre-event soundcheck?

- What is included in your total speaking fee? Some common additions among speakers include book copies, workbooks, post-event coaching or consulting, or access to the speaker’s online coursework.

- At what point will you consider the scope exceeded? This can be based on work produced, hours expended, or both.

Pro Tip: Be extremely detailed when describing the scope of your work with a client. Among speakers – and even among our own team members – scope creep is one of the biggest challenges to overcome. To avoid this in your own business, strive to be clear and confident about the scope of your work. Then, if and when clients push to exceed that scope, stand your ground and calmly remind them of the fees required for out-of-scope work.

Outline any nonexclusivity or confidentiality agreements.

Last but not least, when writing speaker contracts, include sections for nonexclusivity and confidentiality agreements. The former of these, nonexclusivity, protects you in the event that you use material from a presentation multiple times. The latter, confidentiality, can either allow or prevent you from sharing information about a given event.

Although most clients are nonexclusive and non-confidential, there will always be exceptions, especially if you’re in a sensitive industry, such as security or governmental events. To write nonexclusivity and confidentiality agreements into your contracts, consider your unique focus and aim to answer the following questions.

- Will you customize any of your work specifically for this client?

- For any non-customized work, will you reserve the right to use it again with future clients? (Hint: Yes, you definitely should.)

- Will you reserve the right to work with any future clients, even if they’re competitors to this client? (Hint: Again, yes, you should.)

- What types of work does the nonexclusivity and confidentiality aspects of the contract protect? Your presentation slides? Audio and video recordings? Your companion resources (workbooks, courses, etc.)? All of the above?

Pro Tip: In addition to this section, don’t forget to include a section for “Intellectual Property.” While nonexclusivity agreements allow you to use the same material with more than one client, intellectual property agreements protect content that you created so no one uses it without your permission. Remember: You’re an expert first and a speaker second, making your intellectual property a foundational piece of your speaking business.

Examples of Speaker Contracts

Hopefully, this quick and easy guide helps you close your next speaking gig with confidence that you’re protected, from a legal standpoint, and valuable, from a business one (because you are, even if you’re not totally convinced yet). 🙂 For more information about writing speaker contracts, check out the following examples.

Wonder.Legal Speaking Engagement Agreement

The longest and most thorough in this list, Wonder.Legal’s speaking contract template covers almost all of the topics we touched in this blog. Although you’ll need to customize it to suit your speaking business, specifically, it’s a solid starting point for a legally-sound contract. It also provides a few additional sections that can be helpful in less-than-ideal circumstances. These include guidelines for indemnification and conflict resolution, for example.

SpeakerMatch’s Contract Example

Unlike the Wonder.Legal template, SpeakerMatch’s contract example is based on a real-life example, specifically James Donaldson. It covers the basics of a speaking agreement, such as fees and deposit requirements but does not go into depth for the more complex components of a contract. It doesn’t mention project scope, for instance, as well as details about pre-, mid-, and post-event support. Consequently, though this example is an acceptable base for writing speaker contracts, I would recommend supplementing it with the additional sections we’ve covered in this guide.

Dr. Tracy Bennett’s Contract Example

The third template, also based on a real-life speaker’s business, is relatively short compared to the previous examples. Like them, it covers a fair amount of the basic information required for a speaker contract. It also provides an exceptional template for outlining products and services included in the contract.

That said, Dr. Bennett’s base contract does leave out a great deal of the complex definitions required to truly protect the speaker and their client in the event of a misunderstanding or disagreement. For example, it doesn’t mention where legal recourse would take place. Considering this, I also recommend you supplement this template with the sections we’ve covered in this guide.

Note From the SpeakerFlow Team: Please note that although our main goal is to provide as much high-quality, speaker-specific content as possible, in the case of speaker contracts, we also recommend you consult with a legal professional directly. That way, you can be certain your contracts are airtight. 👍